I write about the Norwegians and other Germanic people's origins

Monday, 26 December 2011

The origins of runes

All runic finds from the Danish bogs and graves, approximately dating from the period 160- 450, have been found in a context that clearly shows Roman connections. The bog-deposits contain Roman goods, as do the graves. Runic finds thus emerged either from a military context or a luxurious, aristocratic, context. In both cases the objects were prestige goods. The runes on the bogfinds were carved on objects that may be linked to the top of the military hierarchy (Ilkjær 1996a:70). It appears that Germanic weapons were inscribed in a similar way as Roman weapons (Rix 1992:430-432). At the time of the Marcomanni wars (161-175), contacts were established between the area of the Lower Elbe and the area of the Marcomanni. An elite from the Lower Elbe region migrated southwards and settled in the Marcomanni region (Lund Hansen 1995:390). The Danish elite from that same period must be seen in relation to Germanic vassal kings, who were, highly Romanized, living near the limes of Upper Germany/Raetia (Lund Hansen 1995:390), the region of the Marcomanni, Quadi and Iuthungi. The presence of Ringknauf swords in a warrior grave on Jutland and in deposits of the Vimose bog indicates that there were contacts with Central Europe. These second century swords are typically provincial- Roman products, and the owners, like the man from the Juttish grave of Brokær, must have taken part in the Marcomanni wars. The swords in the Vimose bog belonged to attackers from the South. The sites where these swords were found show that the route was from the Danube northwards along the Elbe (thus crossing the region of Harii and Lugii). At the same time Himlingøje (Sealand) emerged as a power-centre. Here, silver bocals with depictions of warriors holding Ringknauf swords point to the connection with the Marcomanni region (Lund Hansen 1995:386ff.). Ilkjær (1996b:457) mentions the princely grave from Gommern (Altmark, near Magdeburg, the region of the -leben placenames), which, although about a century younger, can be seen as 48 a parallel to the rich Illerup deposits. Parallels can also be detected between deposits in the Vimose and Illerup bogs concerning the collections of silver shield-buckle fragments, the pressed foil ornamentation, face-masks, weapons and military equipment. These objects mark the high military rank of the owners. Outstanding silver shield-accessories emphasize the extraordinary rank of the Germanic elite. The same custom can also be observed in lateantique Gallia, in the warrior grave of Vermand, who, by the look of his shield-accessories, was a Germanic princeps in Roman service (Ilkjær 1996b:475). Among the Illerup material of bronze and iron shield-buckles, Ilkjær notices parallels with finds from Vimose and gravegoods from Norwegian graves (Ilkjær 1996b:475). These belonged to warriors of a lower standing. An analysis of the pressed foil ornaments on the silver shields proves the close connection; the shields must have been produced in the same workshop, by Niþijo, according to Ilkjær (1996b:475). Shield-accessories like these can only be found in excessively rich graves, such as those from Gommern (Germany), Musov (Czechia), Avaldsnes (Norway) and Lilla Harg (Sweden). Therefore, the Prachtschilde from Illerup represent the very top of the elite (Ilkjær 1996b:476). He assumes this elite conducted the trade in Roman military goods (Ilkjær 1996b:477). Without these Roman goods, the extensive wars that preceded the huge offerings in the bogs, would not have been possible. The elite that organised these wars proliferated themselves by 'barbarizing’ the Roman equipment and by decorating them in a Germanic way, which was done in Germanic workshops (Ilkjær 1996b:478). Thus, although the goods make a thoroughly Roman impression, the ornamentation is indigenous, producing a splendid combination of Roman and Germanic culture. Laguþewa was one of the leading princes, according to Ilkjær (1996b:485), because of his shield with gilt-silver pressed foil and precious stones; a rich horse's garment probably belonged to him as well. Wagnijo and Niþijo were war-leaders, too, according to Ilkjær (1996:485), a statement I cannot agree with, since they were most probably weaponsmiths. The runes on several bog finds are not only found on the most precious objects, but also on humbler things such as the wooden handle for a fire-iron (Illerup V) and the comb (Vimose V).

The inscriptions on the lanceheads can directly be connected with the elite, since they controlled the production of these weapons (Ilkjær 1996b:481). From analyses of the pressed foil and pearl-wire ornamentations, it was concluded, on the basis of their highly artistically uniform nature, that there must have been extensive communication with jewellers in Central Europe. The quality of the Thorsberg finds, for instance, points to strong Roman influence. This influence is shown by the use of certain precious stones and the use of mercury (Ilkjær 1996b:481f.).

In the meantime, in the Danish areas of eastern Sealand and Funen wealth and power accumulated and the possession of gold and silver coins increased. Roman luxury goods were imported, probably over sea via the Lower Rhine, through the Vlie along the North Sea coast, through the Limfjord and so on to the north coast of Sealand (Lund Hansen 1995:389, 408f. and the map on page 388). The commissioners who had sent for the luxury goods knew what they wanted; it was no matter of mere chance what came to the North. This also points to close contacts between the clients in the North and the elites living on the border with the Empire. During the second century, tension grew in the North Sea regions, because of pirate raids by the Chauci. One wonders how safe the route by sea-way really was, but perhaps there were treaties between the Sealand aristocrats and Chauci (and Fresones?), who controlled the North Sea coast.

Most probably there was a relation between political events at the borders of the Roman Empire and several weapon-offerings in South Scandinavia (Ilkjær 1996b:339). The first big attack on South Scandinavia coincides with the Marcomanni wars. The offerings in the Vimose bog (Funen), of which the harja comb formed part, were contemporaneous. The attack on Funen came from the South. Further offerings in Vimose and Illerup of around 200 AD coincide with Germanic attacks on the limes. Now the attackers came from the North, from across the Kattegat. All over Scandinavia, many graves are found that contain a similar inventory of weapons. These graves are contemporaneous with the fall of the limes in the 3rd c. This was no coincidence, according to Ilkjær (1996b:339). The initial period of manufacturing weapons on a large scale was at about 200 AD, coinciding with the organisation of armies consisting of hundreds of warriors. We may suppose there existed a powerful and structural organisation at the time. The aim was not merely raiding for loot, there must have been a real struggle for power (Ilkjær 1996b:337ff.) Among the goods in the Illerup bog was an enormous amount of Roman equipment; this of course could not originate from Scandinavia. The wars, predominantly on Jutland, were fought between Scandinavians. All swords were Roman imports and may be interpreted as evidence for the existence of connections between Scandinavia and the Rhineland, according to Ilkjær (in a letter dd. 16 December 1996).

TO SUM UP

in the 2nd c., Germanic groups from the Lower Elbe region moved South, due to the Marcomanni wars in the region north of the Danube. Van Es mentions the Langobardi and the Goths who moved from regions near the Lower Elbe, the Lower Oder and Weichsel respectively (Van Es 1967:537). At the same time an attack was launched upon Denmark from southerly, continental, regions. Booty from these wars was deposited in the Vimose and Thorsberg bogs. Apparently these southerly attackers had contacts with tribes from Sealand (Lund Hansen 1995:406), which may have had something to do with a conflict between Sealand and Funen.

The alliance between Sealand and continental Germanic tribes may also explain the route of import goods: via the Rhine estuary and the North Sea, since the route over land and via the Baltic will not have been safe. In this way the route (of the propagation) of the runes can also be explored. There were contacts between the Rhine region and the North. One must assume the existence of alliances between several Scandinavian elites and continental Germanic ones, living along the Rhine- (and Danube-) limes, in the region between lower Elbe and Rhine, and south of the Baltic. The intermediaries of certain crafts and knowledge must have been individuals. Ilkjær locates Wagnijo, Niþijo's workshop and Laguþewa somewhere in the south of Norway. They belonged to a political alliance of peoples from several regions along the coast and inland valleys, according to Ilkjær (personal communication). This does not exclude the fact that they may have come from elsewhere, from the Continent. Their coming to the North may have been the result of the weapon trade between the Rhineland and Scandinavia. They belonged to the top of the military elite, as was stated by Ilkjær (see above), and it was the elite that controlled weapon import and weapon production.

A chronology of the origin of runic objects (from major find-complexes) may illustrate these contacts: The enormous weapon export to the northern barbarians may have been the result of a Roman divide-and-rule 35 policy, in order to let the Germanic tribes fight among themselves to satisfy their land-hunger. The wealth of some leaders may have been based on relations with high-placed persons in Rome. The gift-exchange system of precious objects belongs also to this atmosphere. Roman soldiers were not allowed to own their weapons - they were stateproperty. Contrary to this, Germanic mercenaries did own their weapons. Yet, very few weapons have been found in graves; apparently a weapon was a heirloom that stayed on in a family for generations. Captured weapons were dedicated to the gods and deposited in bogs. 50 1. Vimose, Funen, ca. 160 AD, from the South. 2. Thorsberg, Schleswig-Holstein ca. 200, from the South. 3. Illerup, Jutland, ca. 200-250, from the North (but made by southern weaponsmiths!)

Sealand, Jutland, Skåne, gravefinds, 200-275, luxury goods, indigenous.

The gravecontexts, though, were Roman. The runic brooches (of nr. 4) are indigenous, so we may assume the inscriptions were made on the spot. Even here the contacts with continental Germanic tribes may also have played a role. The greater part of the names on the brooches appear to be West Germanic: hariso, lamo, alugod, maybe also widuhudaz (Makaev 1996:63). The Danish armies and the enemy from across the sea, from Sweden and Norway and from North-West Germany, fought each other with the same Roman weapons35. It is not unlikely that this was stimulated by Roman diplomacy. It is a well-known fact that the Romans donated subsidies and privileges to barbarian leaders, the foederati, to keep them in power - with the intrinsic purpose to keep them under control. In exchange for money and goods, the allied Germanic leader had to keep other barbarians away from the borders of the Empire, in order to create a bufferzone. Wars were preferably fought far away from Rome, far away from the limes and without Roman troops (Braund 1989:14-26). It appears that the knowledge of the production of strong iron weapons was not very widespread among the Germanic tribes (Much 1959:84ff.). This probably prompted the import (or the robbing) of Roman swords. Lønstrup (1988:95ff.) states that over 100 Roman swords have been found in the Illerup bog. One part carries stamps and other Roman markings, the other part has no marks, but both typologically and technologically it equals the first part; therefore these were also made in the Empire. These swords may have been bought, captured or obtained as a gift. This last possibility only applies to Germanic foederati near the limes, because they were involved in the defence of the Empire. The hundreds of brand-new swords which have been found in Scandinavia and Germany, and partly also in Poland, must have been obtained as merchandise (Lønstrup 1988:96). It is unclear to what extent the Germanic warriors were equipped with swords at the beginning of our era. Behmer (1939:15) informs us that the Germans knew three types of swords: the one-edged hew-sword, the two-edged short Roman gladius and the long Roman two-edged sword, the so called La Tène III type, which was used by the Roman cavalry. This sword-type was the basis for the Germanic Migration Period sword (Behmer 1939:18). The one-edged sword was actually a big knife, a sax. The gladius is of Roman origin and was imitated by the Germans. Perhaps the puzzling word kesjam on the Bergakker scabbard mount may be explained by the assumption that the weapon designations for both swords and spears were confused. At the time the Bergakker inscription was made (early 5th c.), the word kesja may have denoted a Vennolum is a place in Norway, the findplace of the eponymous lance head. 36 51 certain sword-type; at a (much) later period the word got the meaning of ‘javelin’ (for another interpretation see the Checklist of Runic Inscriptions in The Netherlands). A (vulgar) Latin word for sword was CESA, the equivalent of Germanic *gaizaz (I guess the source was ultimately Celtic).

An element such as Gesa- is found in the names of the Gaesatae and the Matronae Gaesahenae and Matronae Gesationum. A soldier of the Cohors I Vindelicorum was called Cassius Gesatus. According to Alföldy (1968:106) the name Gesatus is a cognomen, referring to the man's weapons. Probably, the Germans took over some special type of sword together with its foreign name. As to the tribe of the Gaesatae (recorded in 236 BC in the Alps), these people may have been Celts, so perhaps gaes- is a Celtic name for a Celtic La Tène sword. The lanceheads of the Illerup bog were of Scandinavian origin, made in Norway, according to Ilkjær, since an analysis of the iron points to iron ore from North Trondelag (personal communication). However, Roman know-how may have been wished for, a knowledge which may have been provided by Germanic weaponsmiths from among the foederati of the Rhine area. The obvious connection, then, is that wagnijo and niþijo learned their craft as weaponsmiths either in their homelands, or as mercenaries in the Roman army, where they also learned to sign their work. Where did they learn to do this in runes? In Norway? Unlikely. They probably learned this together with their craft. A runographic analysis shows a close resemblance between the runic graphs on the lanceheads (wagnijo) and the graphs on the shield handles (niþijo and laguþewa), which points to the same background of the runographers. Niþijo, as is mentioned above, had a workshop, where many of the Romaninspired items, found in the Illerup bog, were manufactured (Ilkjær 1996b:440f.). According to Ilkjær (1993) the lanceheads of the Vennolum-type36, to which the runic lanceheads belong, were widespread in Scandinavia. The runic spearhead from Øvre Stabu (2nd half of the 2nd c.) also belongs to the Vennolum type. Ilkjær states that only a few lanceheads from the Continent show some similarity, and that only one item from Poland is of the Vennolum type (personal communication).

THE FIRST RUNOGRAPHERS

Who could read and write runes in an almost illiterate society is subject of an often recurring debate. If one abandons the idea of a purely symbolical, magical or religious purpose of adding runes to objects, the answer is that at least the former mercenaries had learned to read and write, especially the officers. On the other hand there must have been literate people, more specifically craftsmen, among the foederati. The literate officers and soldiers must have constituted a small group. This would tie in very well with the observance that runic objects are sparse and emerge from widely separated places. Runic writing may have started as a soldiers’ and/or craftsmen's skill. This might explain the curious meaning of the word ‘rune': secret, something hidden from outsiders. The runic legends show very simple information, but it may be that the art of writing was sort of ‘secretive', the prerogative of a specific group only, and not necessarily linked to magic or religion. The application of writing, especially on precious objects points to special artisans. Signing one's name marks the pride of the author, who knows an extraordinary skill. He stands out in society because of his knowledge, and Syrett (1994:141) proposes to view swarta and similar instances, such as laguþewa as West Germanic strong 37 nouns with loss of final *-z. Here one apparently felt inclined to read the later Scandinavian h or A rune, and even a ‘repaired’ n rune has 38 been suggested (see Krause 1996:191, with ref.). 52 therefore obtains a special status. Naturally, he would be very reluctant to pass this knowledge on to others, which would make it more common. Perhaps this also (partly) explains the extreme rarity of objects exhibiting runic writing, dating from the early ages.

THE WEST GERMANIC HYPHOTHESIS

An indication for a West Germanic origin of runic writing is the presence of West Germanic name forms on some of the oldest artifacts: wagnijo and niþijo (see above), harja (cf. Peterson 1994:161), swarta37, hariso, alugod, leþro, lamo (cf. Syrett 1994:141ff.), and also laguþewa. These attestations are from circa 200 AD and somewhat later, found in bogs and graves in Jutland, on Funen and on Sealand. Stoklund (1994a:106) points to the remarkable fact that all inscriptions that show West Germanic forms or which have West Germanic parallels are on weapons that originate from the area around the Kattegat, Scandinavia or North Germany and which were deposited in the Illerup and Vimose bogs. Few would claim that a West Germanic speaking people lived in those areas around 200 AD. But individuals such as weaponsmiths and other craftsmen, descending from a West Germanic speaking area, may very well have been present there. Especially the names ending in - ijo seem to point to the region of the Ubii in the Rhineland, since this was a productive suffix in Ubian names (Weisgerber 1968:134f.). The problem of the a- and o- endings, present in the nominative forms of apparently masculine names in runic inscriptions found in Denmark, has long been the subject of discussion. Syrett (1994:151f.) concludes that the early evidence, e.g. up to c. 400, "clearly indicates that -o and -a could be used side by side to represent the masculine n- stem nom. sg., but in the later period, as exemplified (...) by the bracteates, -a predominates". Herewith the case has not yet been cleared. Perhaps the problem should be tackled from a different angle. An examination of the recorded names of Germanic soldiers in the Roman army shows that the endings -a and -o are quite frequent. It may very well be that names featuring these endings were introduced to the North by veterans and craftsmen, such as weaponsmiths. As has been argued above, wagnijo and niþijo may have originated from the Rhineland, from the tribes of the Vangiones and Nidensis. The owner of the Vimose comb (with runic inscription) may have been a member of the tribe of the Harii, a sub-tribe of the Lugii. The descent of the man who wrote harja on his comb, is supported by a runic inscription on the Skåäng stone in Sweden, reading harijaz leugaz, evidently pointing to both Harii and Lugii. The reading harijaz is based on the assumption that the 7th rune is the z, corresponding with the ‘Charnay’ rune £ representing z. Its ornamental form has as yet not been recognised as the rune for z in this Swedish rune-text38. harja reflects a West Gmc dialect, with loss of final -z in the nominative. Just as in wagnijo and holtijaz the elements ijo and ija may be interpreted as an indication of someone's descent, harja can be interpreted as referring to someone belonging to the tribe of the Harii. A more extended form is the spelling harijaz of the Skåäng stone.

The runes fir?a on Illerup VI may refer to the tribe of the Firaesi (Schönfeld 1965:88). Furthermore, one may 39 speculate as to whether the name harkilaz of the Nydam sheath plate contains a scribal error; perhaps it should represent haukilaz, provided the third rune should be read as u, not r (its shape, however, is that of an 'open’ r rune: _ ). If so, it could be interpreted as a reference to the Chauci. Besides, ON hark- ‘tumult’ is difficult to explain as a name-element. 53 suggested that the second part of this inscription leugaz was derived from the tribal name Lugii. Apparently Krause (1971:163) and Antonsen (1975:66) were not aware of the possibility of finding a tribal name here. The name Lugii appears to be related to Go *Lugj©s (Much 1959:378) and Go. liugan 'to marry', actually 'to swear an oath'. The root *leugh-, *lugh- ‘oath’ is only attested in Celtic and Germanic (Schwarz 1967:30). The Lugii, according to Much (1959:378), were a group of tribes, probably unified by an oath. The Harii lived in North Poland, not far from the Baltic. The comb may well have originated in that area, because of its find-context, which, according to Ilkjær (1996a:68), consisted of a combination of certain Polish fire-equipment "Indslag af pyrit og evt. polske ildstål", buckles with a forked thorn, and combs consisting of two layers, such as is the case with the harja comb (cf. the map in Ilkjær 1993:377 and further on the text on pp. 376-378). 7. Conclusions The Skåäng inscription supports the interpretations of wagnijo, niþijo and harja, as being appellativa referring to certain tribes, and not just personal names. According to Bang (1906:- 48f., note 419), Germanic PNs are often derived from tribal names. Other instances are the Hitsum (Friesland) bracteate (approximately around 500 AD), with the legend fozo, a PN, which may have been derived from the tribal name of the F©si (cf. IK, nr. 76, and the Checklist of Bracteates with Runes in the Catalogue), and the Szabadbattyán brooch, with the legend marings (see nr. 36 in the Checklist of Early Danish and Gothic inscriptions).

As to tribal names (attested in the Roman period) on Scandinavian stones, we have the forms haukoþuz (Vånga), hakuþo (Noleby). It may be useful to investigate once again the possibility, whether here the Chauci are referred to. Further there is ekaljamarkiz baij?z (Kårstad), perhaps pointing to the Bavarians? swabaharjaz (Rö) may refer to the Suebi, living on the right bank of the Rhine, iuþingaz (Reistad) to the Iuthungi (South Germany, north of the Danube), saligastiz (Berga) perhaps to the Salii (near the lower Rhine). Birkhan (1970:170, note 243) suggests the patronymic wagigaz on the Rosseland stone may contain the PN Vangio39. If these assumptions are correct, the inscriptions on the above mentioned stones may be dated rather early, on historical grounds, to between 200 and 500 AD. If wagnijo is exactly to be pronounced as Vangio, one has to accept the fact that the sequences of -gn- and -ng- both represent the sound [h]. In Roman ears the Germanic cluster gn may have sounded like ng. At any rate, the spelling of the tribal name Vangiones is in accordance with Latin practice. The same applies to the Roman spelling of the folk name Nidenses. Since the Romans did not know the graph þ, they most likely would write a d between vowels. Therefore, Nith- may be rendered Nid- in Roman orthography. Cf. also the cognomen Sinnio, a Germanic member of the corpore custos Drusinianus (Bellen 1981:73ff., note 40 105; and Weisgerber 1968:135, and 393f.). It may be that Sinnio shows West Gmc consonant-gemination, but on the other hand it might just reflect the name of the Roman gens Sinnius. 54 At some time in runic history there existed a rune W_to represent the sound [h], but it is not used to represent the sequence gn in wagnijo. Moreover, the carver applied W to render w: hence the (i)ng rune W may not yet have been present in the runic alphabet of around 200 AD. ¨

Masculine names ending in -io, n- and jan- stems, were especially frequent in the region of the Ubii, who were neighbours to the Vangiones. The names ending in -io reflect Germanic morphology representing the Latin ending -ius. The suffix -inius was reflected by Germanic - inio- (Weisgerber 1968:135, 392ff. and Weisgerber 1966/67:207). Weisgerber mentions the fact that within the n- stems of all IE languages we also find the on- type, which occurs in specific cases such as ion-, a type that is often met with in personal (Germanic) names (Weisgerber 1968:392). "Das Naheliegen von -inius bestätigt auch für das Ubiergebiet die Geläufigkeit der germanischen Personennamenbildung gemäß der n- Flexion. Mit dieser ist im ganzen germanisch-römischen Grenzraum zu rechnen. Die angeführte Reihe Primio usw. ist herausgehoben aus einer Fülle von Parallelbeispielen: Acceptio, Aprilio, Augustio, Faustio, Firmio, Florio, Hilario, Longio, Paternio usw." (Weisgerber 1968:394). In fact, in this way the question of the problematic ending -ijo in masculine PNs may be solved40. The awkward ending -a of laguþewa (cf. Syrett 1994:44f.) can be solved by accepting the fact that the name may indeed be West Germanic. Syrett states that even weak masc. forms such as swarta may be taken as West Germanic strong nouns, the "precursor of ON Svartr" (Syrett 1994:45). There is no need to postulate the presence of a runic koiné, such is suggested by e.g. Makaev (1996:63). He stated that: "Therefore the runic material, [...] provides important and elegant, albeit indirect, support for our hypothesis on the West Germanic-Scandinavian dialectal base of the runic koiné". One may simply change the term ‘runic koiné’ for ‘West Germanic origin of runic writing'. I cannot yet estimate the implications of the fact that the frequent occurrence of runic leub (and leubo, leuba, leubwini, lbi, leob, liub) in 6th century Germany may be connected with the many Leubo's in the area of the Ubii in the Roman period (Weisgerber 1968:150f., 167, 374f.). The name is also found among the Tungri and along the Lower Rhine. A runic attestation of the name is found in Västergötland, Sweden, on the SKÄRKIND stone: skiþaleubaz. This may refer to a Rhenish merchant of skins (containing the element ski(n)þa- ‘skin'). Another example is liubu (OPEDAL), but this may be no PN, but an adjective, or a verbform.

To sum up:

In view of the presence of (1) West Germanic name forms on the oldest runic attestations, and (2) the provenance of some of these objects, in combination with (3) the origin of the weaponsmiths wagnijo and niþijo, one may conclude that runic knowledge was first known on the Continent. (4) The inscriptions harja on the Vimose-comb and harijaz leugaz on the Swedish Skåäng stone confirm a connection between the North and the continental tribes of the Harii and the Lugii. (5) The presence of certain elite-weapons and -equipment in the Danish bogs is indicative of a network of contacts between elites from Scandinavia and the 55 Continent, and especially with provincial-Roman regions. The use of runes is closely linked to these relations. During the second century runic writing must have spread to the North. This is demonstrated by the runic brooches of Sealand, Jutland and Skåne, which were local products. The inscribed Vennolum-type lanceheads, including the lanceheads from Øvre Stabu and Gotland point to the possible presence of runic knowledge in Norway and Sweden, presumably taken there by Rhenish smiths. The weapon-trade between the Rhineland and the North may serve as evidence for close connections. I suggest the runic script was first developed in Romanized regions along the Rhine.

SOURCE: Runes around the North Sea and on the Continent AD 150-700, by J. H. Looijenga, 1997.

Wednesday, 12 October 2011

Haplogroup Y-R1b in Norway

The Norwegian Dna-project (Familytree DNA), concluded that 56 of the men tested belong to haplogroup R1b (ca. 30% of the population). R1b can be split into several undergruops called clusters.

27 of them belong to R1b1a2. This type is common in Western Europe. In Norway, this type is mainly found in coastal areas.

16 other men belong to cluster R1b1a2a1a1b4. This cluster is associated with Celtic tribes and reaches a maximum in Britain and Ireland (25-30% of all males). In Norway, this type is found near the West and South coasts.

7 other men belong to cluster R1b1a2a1a1b. This cluster is common west of the Rhine Basin.

5 other men belong to cluster R1b1a2a1a1a and R1b1a2a1a1a4. These clusters are common in North West Europe, especially in the Netherlands.

1 man belong to cluster R1b1a2a1a1b3. This type is common in Western Europe.

Tuesday, 11 October 2011

Ancient Roman artifacts discovered in Norway

Archaeological findings have strengthened notions amongst scholars that quite a few Norwegians, from the farthermost north of Europe, in all likelihood served as soldiers in the Roman legions.

Ancient weaponry, cups and coins all points towards a more extensive cultural exchange between Norway/Scandinavia and the Roman Empire than previously assumed, an assumption, (article in Norwegian only), Professor Heid Gjøstein Resi at the Cultural Historical Museum, at the University of Oslo also seems to agree with.

Yes, I believe Norwegians served in Roman legions," he says, and continues;"We have been able to confirm that artifacts found in old graves in Norway, which at first were believed to have originated elsewhere, do indeed have their origins from the Roman Empire."

In 1895, during the excavation of the grave of a Norwegian warlord, dating back to 200 A.D, buried near the little village of Avaldsnes on the west coast of Norway, scientists found a sword with a silver ornamented scabbard, a silver ornamented shield, bracelets and four gold rings, artifacts and weaponry that indicates very well that this warlord might have served in the Roman legions, according to Professor Lotte Hedeager at the Institute of archeology, Oslo University.

It is a well known fact that people from so called barbaric tribes like the German tribes up north, were recruited into the Roman legions and that some of them even ended up as Generals and leaders of the Roman legions themselves.

Ancient Roman artifacts found in a grave

in the Norwegian county of Østfold

(Photo: Eirik Irgens Johnsen, Cultural

Historical Museum, University of Oslo)

(Click for larger image)

"Warriors that chose to return to Norway, after 10-15 years in service, brought back not only Roman artifacts and coins but some even brought back artifacts typical for a man serving in the legions," says Laszlo Berczelli, a retired scholar from the Cultural Historical Museum.One artifact typical for soldiers in service of the Roman army was vessels made of bronze for drinking and eating, an artifact found in many graves excavated in the eastern parts of Norway.

On an ending note, the scientist Svein Gulli, at the Cultural Historical Museum, asks somewhat rhetorically;

"It is a historical fact that Vikings served as mercenaries in the service of the Byzantine emperor, why then couldn't they have served in the Roman legions?"

Wednesday, 28 September 2011

The tribe of Segni – Sygner

BACKGROUND

The Segui and Condrusi, of the nation and number of the Germans [Germani], and who are between the Eburones and the Treviri , sent embassadors to Caesar to entreat that he would not regard them in the number of his enemies, nor consider that the cause of all the Germans on this side the Rhine was one and the same; that they had formed no plans of war, and had sent no auxiliaries to Ambiorix. Caesar, having ascertained this fact by an examination of his prisoners, commanded that if any of the Eburones in their flight had repaired to them, they should be sent back to him; he assures them that if they did that, he will not injure their territories.

These tribes are referred to as the "Germani Cisrhenani", to distinguish them from Germani living on the east of the Rhine, outside of the Gaulish and Roman area. Whether they actually spoke a Germanic language or not, is still uncertain. The region was strongly influenced by Gaul, and many of the personal names and tribal names from these communities appear to be Celtic. But on the other hand it was claimed by Tacitus that these Germani were the original Germani, and that the term Germani as it came to be widely used was not the original meaning. He also said that the descendants of the original Germani in his time were the Tungri.[3]

The general area of the Belgian Germani was between the Scheldt and Rhine rivers, and north of Luxemburg and the Moselle, which is where the Treverii lived. In modern terms this area includes eastern Belgium, the southern parts of the Netherlands, and a part of Germany on the west of the Rhine, but north of the Moselle, which was Treverii territory.

The specific location of the Segni, as can be seen from the brief mention of Caesar, quoted above, was between the Eburones and the Treverii, somewhere in the region of the Ardennes. The Condrusi, mentioned as living in the same area and being part of the same embassy to Caesar, are thought to have lived in the Condroz region in the north of the Ardennes.

In the 19th century, it was sometimes claimed that the name of the Segni is preserved in a modern town of "Sinei or Signei", on the Meuse river, in the Belgian province of Namur.¨

The Sygnir were a tribe in Western Norway who settled in the area known as Sogn. It is most likely that this area was settled by migrants from North West Europe, of Gaulish-Germanic descent.

Monday, 26 September 2011

Norwegian DNA Results

Either because of late glacial or of more

recent migrations the Norway Y chromosome gene pool

appears to be very close to present day Germans. In fact

the Fst and the Fst data indicate Germans and a few other

Central European populations as being the closest to the

Norwegians. When we compare our results with those

based on different polymorphic systems,9,17 we can infer

that these conclusions are also valid for Swedish, while

Finns and Saami had a quite different genetic history with

a great impact of Uralic Finno-Ugric speaking population.

The mtDNA polymorphisms had previously shown the

genetic closeness of Norwegians with Germans, based on the statistic r.8

Our data are consistent with this finding

and support the Y chromosome representation of a strong

genetic influence from central European groups, although

it is less quantifiable.

(Different genetic components in the Norwegian population revealed by the analysis of mtDNA andY chromosome polymorphisms)

According to Cavalli-Sforza, the closest related populations (By genetic distance) are: Germans (13), Dutch (13), Danes (14), Swedes (15), English (16).

NORWEGIAN Y-DNA HAPLOGROUPS

The Norwegian R1a varies between regions. It ranges from 13% in the South, to 19% in the South East near Oslo. It’s maximum is at 31% in Trøndelag.

This type can be split in several undergroups.

R1b is another major haplogroup. This ranges from 26% in Eastern Norway, and the North, to 44% in the West and South. One noticeable thing is that it is a lot more common near the coast than far inland.

I1 is the most common haplogroup on average in Norway, but it varies regionally. It’s lowest percentage is found in the West, 30%. In the North it is 34%. In the South, South East near Oslo, and Trøndelag it is 39-42%.

Halogroup N3 is found at 10% in the North, and a very low percentage in the East and South East. This haplogroup is typical of Finnic-Ugric speakers.

MY SUGGESTION TO HOW THESE HAPLOGROUPS CAME TO NORWAY.

R1b is also most common in Norway, although most common in the West and South, and more found near the coast then inland. I suggest that early settlers brought this type with them. These tribes, who migrated from the Continent abt. 400BC, settled mostly in the West, South and South East. This is the most R1b rich area of Norway. It is likely that these Germanic tribes also brought haplogroup I1 with them. This is the most common haplogroup in Norway. It is noticeable that this type is more common inland than near the coast.

The Norway Y chromosome gene poolappears to be very close to present day Germans (Report by Cavalli-Sforza, 2007).

Tribes of the Goths came to Norway abt. 100AC. They brought the Norse religion (Asatrui). My thesis is that these people brought most of the R1a DNA (Particularly the M17 marker) to Norway.

The Raetians and Noricians

Cladius started building roads through the Alps to the Donau border 49AC. He deported the Norician leaders, a Celtic people also called Hades. The inhabitants of Noreia, Teurnia and several other cities were deported 41-50AC. The Romans did they same in the province of Raetia (Modern Switzerland).

Dio Cassius wrote ca. 200AC about the history of the Roman Empire:

- Raetia had a large population of men who could fight and carry weapons, so the majority of military aged men had to be deported in order to make the area safer to travel through. Large areas were empty of people after the deportations. Cassius does not tell anything about were these people were sent, but those who were too old for military service, were used as slaves. (12). It is likely that they were sent where the Romans needed them the most.

THE EINANG STONE

Einangsteinen is a stone located in Slidre, Valdres (Norway). It’s got an inscription on it, written like this (translated into the latin letters):

DAGARTHARRUNOFAIHIDO

The Raetians and the Venetians used almost the same alphabet, but they used different languages. The Venetians started using points in between the words to seperate them. The Raetians dit not. That’s how you can see if an inscription is done by a Raetian or a Venetian. They inscription on the Einang stone haven’t got any points, it could be Raetian.

Ratroromansch is a language used by a minority in Switzerland today. By using a dictionary, one can seperate the sentence into the following words:

DA GARTHAR RUNO FAINIDO

Translation:

Da Garthar (Eng. Do watch , look after)

Runo (Eng. Field)

Fainido (Eng. Hay crop).

So the inscription means : DO WATCH THE FIELD AND THE HAY CROP

Professor Dr. Helmut Rix writes “It is certain to anyone who knows the alphabets used in Northern Italy the last centuries BC, that they are the source of the Germanic Runs.

Dr. Sybille Haynes writes “The Etruscan alphabet originated in Greece and spread to Central and Northern Italy, and northwards to the Germanic people, who called it Runs. “

(Sybille Haynes. Etruscan Civilization. British Museum Press 2000.)`

The inscription tell us about a people who had to leave a safe life in the Alpine valleys. These people risked their lives by starting from scratch. If the crop failed, the cattle would die, and the humans would follow. That’s why they prayed to their gods for assistance.

DID THE RAETIANS SETTLE DOWN IN NORWAY?

The –ar ending in “Garthar”, suggests that the dialect is from Lower Engadin. The dialect and the valley is called Vallader, which sounds a lot like Valdres, the valley in Norway.

The Romans annexed Raetia and the kingdom of Noricium during the reign of Keiser Augustus 15AC. He had roads built through the Alps to the Donau border. To make this area safer to travel trough, the Romans deported most men who could carry weapons. (Dio Cassius Cocceianus: Historia Romana LIV, 22.)

These men were trained as soldiers and a lot of them were sent to the support troops in England. The Raetians were common members of these troops.

Soldiers retired after 25 years of service. They were given a Roman citizenship, and the choice of a lump sum of money or a piece of land. Those who chose the latter were given it, where the Romans wanted a Roman-friendly population. The Raetians settled down in England, Norway, West-Sweden, Jutland (Denmark), Northern Germany and Holland.

The inscriptions at Einang could have been made by a Raetian who, after finished millitary service got a piece of land there. After the work of clearing the land, he would inscript a prayer to the gods. He would know the latin alphabet, being a Roman soldier.

The inscriptions in the Furtharch alphabet are found all over Norway. That means that these soldiers where placed all over the country.

Archaeological discoveries of soldier graves with Roman weapons are found in Norway. The weapons are those of a Roman support troop. It is unlikely that they were native Norwegians. A Roman support soldier could not have been a slave, and a Roman citizenship was necessary in order to be recruited. The Romans would also avoid using a country’s native inhabitants as soldiers, fighting against their own people (21).

RAETIAN VERSUS NORWEGIAN LANGUAGE

A language and place names can tell a lot about where a people has got its origins. The spelling and pronunciation do vary a lot between countries and even regions. But with a little bit of local knowledge, connections can be found. Here are some examples of similar sounding words in Raetian Romansch and Norwegian.

| Raetian / Romansch | Norwegian | Meaning |

| Schliere | Slidre | Where two valleys meet |

| Baito | Beito | Cabin |

| Lej Ra | Leira | Where a lake ends |

| Bagno | Bagn | |

| Ble | Blefjell | Ble – moor |

| Godbrenta | Gudbrandsdal | Forest valley |

| Lescha | Lesja | Entrance (door) |

| Tovre | Dovre | Windy place |

| Ota | Otta | Upper |

| Sel / Sil | Sel | Forest |

| Vaugod | Vågå | Where you cross a river |

| Sio-ch | Skjåk | Upper or highest |

| Vriun | Fron | Place of defence |

| Vintsra | Vinstra | Area – Val Venosta |

| Laugen | Lågen | River |

| Vaz | Vats | Place in Graubunden |

| Savogn / Sogn | Sogn | Sacred place |

| Peis | Peis | Fireplace |

| Vad / Vau | Vad | Where you cross the river |

| Bläss | Bless | White spot to mark the animals |

| Brascha | Brasa | Fire |

| Buordi | Byrde | Burden |

| Cherin | Kjerring | Wife / woman |

| Korv | Korp | Raven |

| Crösch | Krok | Crook or latch |

| Fliar | Fli | Getting dressed |

| Ingün | Ingen | Nobody |

| Maugliar | Maule | Eating |

| Muoch | Møkk | Dirt |

| Mort | Mørkt | Dark |

| Rar | Rar | Funny |

| Regla | Regle | Rime |

| Dret | Rett | Straight |

| Ria | Ri | Ride |

| Sön | Søvn | Sleep |

| Squit | Skvett | A little of milk or water |

| Cratschlar | Skrasle | Laugh |

| Stachar | Stakkar | Poor person |

| Tagliar | Telje | Axe |

| Trev | Trev | Beams |

| Truoch | Tråkk | Path |

| Ovazun | Ofsen | Overflow |

| Biestga | Beist | Animals |

| Vurdar | Vurder | To think |

| Trel | Træl | Someone who struggles |

| Scurv | Skurv | Hill |

| Schmievler | Smuler | Crumpets |

| Stizi | Sti | Path |

| Rond | Rondane | The big mounains |

| Fil | File | A mountain with a road through |

| Egga | Egga | Edge |

| Juf | Juv | Very narrow valley |

| Fly | Flya | Mountain Plateu |

| Eng | Eng | Field |

| Quinda | Kvinda | River name (Amden, St. Gallen) |

| Seere | Sire | A place with two farms |

| Grut | Grøt | Place name |

| Windeg | Vindegg | Place name |

Sources:

Bok a. : Oscar Peer: Dicziunari rumantsch ladin – tudais-ch.

Lia Rumantsch, Chur, Sveits. 1968.

Bok b. Reto Bezzola u. Rud. Tönjachen.

Dicziunari tudais-ch – rumantsch ladin. Lia Rumantscha 1944

Bok c. Bernardi, Decurtins, Eichenhofer, Saluz, Vögeli :

Handwörterbuch des Rätoromanischen.

Societa Retorumantscha und Verein f. Bündner Kulturforschung.

ISBN 3-907-495-57-8.

Thursday, 8 September 2011

Wednesday, 20 July 2011

The Limburg connection – The Eburones

The Eburones (Greek: Ἐβούρωνες, Strabo), were a Belgic people who lived in the northeast of Gaul, near the river Meuse and the modern provinces of Belgian and Dutch Limburg. Eburo means Yew Tree and perhaps the suffix onna = "divine" meaning "The people of the Sacret Yew. It was tabu to damage the sacred trees and assemblies were held under them. The Eburones played a major role in Julius Caesar's account of his "Gallic Wars", as the most important tribe within the Germani group of tribes east of the Rhine. The name of the Eburones was wiped out after their failed revolt against Caesar's forces during the Gallic Wars, and whether any significant part of the population lived on in the area as Tungri, the tribal name found here later, is uncertain.

Ancient stone carvings

Carvings of yew trees and ships are found several places by the Norwegian coasts. This example is from Skjeberg. The ships carved into the stone are the same kind as used by the Rhine and Meuse appr. 500 BC. The yew tree was the tribal tree of the Eburones.

Language

Limburgs is today a German dialect, spoken in the Limburg province. It is a two-toned language. Two-toned languages are rare in Germanic languages, only used in Swedish, Norwegian, and Limburgs.

Place names

Swulgen is situated in the Meuse-valley near Venlo. In Norway, you will find Svelgen in Sogn on the western coast.

Names ending in -lo, like Almelo, Venlo, Baarlo. -lo names are found in Norway, such as Oslo, Byrkjelo, Varlo.

Hasselt is a city in Limburg. Norway has got Hassel in Nordland.

Names ending in -beek, like Spaubeek, Neerbeek. -Beek (English: grove, river) are found all over Norway.

Names ending in -Holt are very common both in Limburg and Norway.

Worm is a river that runs between Aachen and meets the Ruhr by Heinsberg. Norway has got the river Vorma by Eidsvoll.

Dremmen is a place situated near Heinsberg. Norway has got the town Drammen.

Porselen is situated near Dremmen (Limburg). Norway has got Porsgrunn in Grenland.

Ringselven is situated near Weert. Norway has got names like Ringerike. Names ending with -elven (English: River) are extremely common in Norway.

Lier is situated south of Antwerpen in Flanders. Norway has got Lier near Drammen.

Laukdal is situated near Westerlo in Flanders. Names ending with -dal are extremely common in Norway. Bergom and Asberg are also found in the same area. Names ending in -berg are also extremely common in Norway.

Koll. Kollenberg is situated near Maastricht in Limburg. Names containing –Koll are very common in Norway.

Roa. This name is common in Norway, sometimes pronounced Roi in old-Norwegian. Limburg has got Kinrooi, Roermond.

Son is a town near Eindhoven. Norway has got Son, a river and town in the south east near Oslo.

The migration of Gallia-Belgic tribes

The Belgae were a group of tribes living in northern Gaul, on the west bank of the Rhine, in the 3rd century BC, and later also in Britain, and possibly even Ireland. They gave their name to the Roman province of Gallia Belgica, and very much later, to the modern country of Belgium.

Julius Caesar describes Gaul at the time of his conquests (58 - 51 BC) as divided into three parts, inhabited by the Aquitani in the southwest, the Gauls of the biggest central part, who in their own language were called Celtae, and the Belgae in the north. Each of these three parts were different in terms of customs, laws and language. He noted that the Belgae, being farthest from the developed civilization of Rome and closest to Germania over the Rhine, were the bravest of the three groups, because "merchants least frequently resort to them, and import those things which tend to effeminate the mind".[6]

Ancient sources such as Caesar are unclear about the things used to define ethnicity today. He describes the Belgae as both Celtic (or at least Gaulish) and Germanic (at least some of them, and at least by descent).

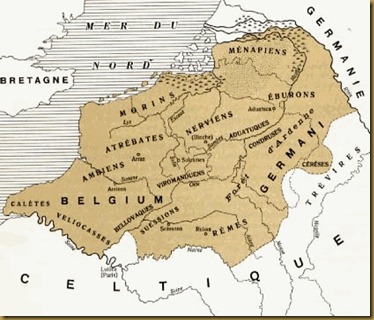

A map of Gallia Belgae

MigrationsA Focean sea captain wrote this about the abandoned areas by Schelde and Mösa (550BC) :

..." Because of Celtic tribes who are constantly in war, the land is abandoned. The natives, migrated to the places where they settled most densely. These areas are mountainous, naked cliffs and mountains that raises towards the sky"...

Pomponius Mela wrote 41AC about a sailing route from Gibraltar northwards by the Atlantic Ocean. Furthest north is Thule and Mela. He wrote:

"... Thule is situated north of the Belgian coasts. The nights are extremely short here during the summer because of the late sunset. These areas are close to Asia, and the people here are almost exclusively of Belgian stock. In the far north of this country, the sun is completely absent during the winter. It’s also constantly light during the summer. The country is narrow, quite sunny and quite fertile. The inhabitants are civil and live long and happy lives. They enjoy festivities and they neither quarrel nor fight…

Plutharch tells abt. 100AC about Camillus, the Roman king (446-365 BC). He writes about a migration northwards:

..."The Gauls are of the Celtic race, and are reported to have been compelled by their numbers to leave their country, which was insufficient to sustain them all, and to have gone in search of other homes. And being, many thousands of them, young men and able to bear arms, and carrying with them a still greater number of women and young children, some of them, passing the Riphaean mountains, fell upon the Northern Ocean, and possessed themselves of the farthest parts of Europe

The Riphean mountains mentioned, could be the west coast of Norway.

Dio Cassius writes the following 200AC :

"... The Belgae lives in several tribes by the Rhine and areas by the sea opposite Britain".¨

NORWEGIAN REGIONS

Trøndelag. This name can be seperated into Trønde-lag. Trønder is a germanistation of the latin Treueri, Treu-eri. The Treueri were of the largest tribes in Gallia-Belgae. They dwelled between the Rhine and the Meuse (Mosel). Their capital, Trier by the Meuse, was a roman city. The second part in Trøndelag, -lag, (English: Law) means that the Treueri's laws were used. Trøndelag was a colony settled by the Treueri.

Møre. Møre might come from Latin Mare, meaning ocean. The Morini were a tribe in Gallia-Belgica dwelling by the coast. In Norwegian it is spelled Møre. The Morini could have settled in Møre on the West coast of Norway.

Gulen is situated on Norway's west coast. Locals pronounce the name as "Gaulen". The name suggests that this was a Gaulish country.

Hadeland. This region is in the South-East of Norway, with Gran in the centre. The Hadui were one of the major tribes in Gallia-Belgica. The name Hadeland suggests that the Hadui settled here.

Grenland is situated in the South-East of Norway by the sea. This region could be named after the Gallia-Belgae god Gran. The old name on the sea here was Gran-Marr, named after the Gaulish god. After the Christianisation of Norway, his name became a taboo.

River names

The Mösa or Meuse as it is spellt today, springs out west of Vogese and continues through France, Belgium and Holland before it ends in the North Sea. The Norwegian river Mjøsa is pronounced the same way as the ancient Mösa.

The Vair river is an offshot of Meuse (Near Neufchateau). The name Vair sounds like the Norwegian Vær. Vær-dalen is a valley in Trøndelag.

The Chieur river runs westwards and ends up in the Meuse south of the Belgian border. Chieur is pronounced like the Norwegian Stjør. Stjørdalen is a valley in Trøndelag.

The Nied runs eastwards, it's source is east of Neufchateau by the Meuse. In Trøndelag, the Nid ends in the sea by Trondheim.

These rivers are all located in the Meuse-valley in the old Gallia-Belgica. That the same river names exists in Trøndelag is not likely to be a coincidence.

Gaulish gods in Norway

Gran (Roman: Grannus) was one of the gods of ancient Gaul. He healed the sick and was a sun-god. A pine tree was his symbol (Pine = Gran in Norwegian). He was worshipped near rivers, and he's main place of worship is today called Grand and is situated 20km north-west of Neufchateu by the river Meuse. Another place of worship was called Aqua Granni and was situated near Aachen.

In Norway Gran exists in place names such as Granvin, Gransherad and Grenland.

Teutates used to be a Gaulish tribal god who was involved in all of the tribes activites, wether it was trading, fertillity or war. The Gaulish pronounciation is thought to be Tota or Tot. Tot expected live sacrifices, usually animals, but in extreme cases, humans were sacrificed. Toten is the name of a region in South-Eastern Norway.

Mösa (Meusel) was personified and worshipped as a female godess by the Gaulish people who lived by the river with the same name. After christianisation in Norway, the word "Mös" became a taboo, since it was the name of a heathen godess.

Language: The Gallia-Belgae spoke dialects that resemble modern Flemish. Flemish is spoken in the Flanders region of Belgium.

Y-DNA profile R1b is the major haplogroup of the male population in Flanders, and the nearby region of Limburg, and North-West Germany. About 30% of Norwegian men are of the R1b haplogroup. This supports the hypothesis of an immigration from the Meuse-valley to Norway. This group may have migrated abt. 600BC.

A Roman presence in Norway:

The book Brittania (Tacitus) tells about a journey where Julius Agricola travels with his millitary troops northwards to the Orkneys and further northeast. He tells:

"... We could see Thule in the distance, where our mission leaded us. The winter was approaching. They say that the ocean here become stiff and impossible to travel on by boat. But I will tell you, that in no other place is the ocean so wide and carries so many streams in all directions. The ocean streams in between mountains and cliffs as if it was a part of it." (11).

Where was Thule located?

Ptolemaios in Alexandria writes the following:

The Northern border (of the inhabited world) is by the degree 63 north of the equator, through the Island Thule (12, 13).

Ptolemaious writes that the summer is 20 hours long mid-summer in Thule. This is correct for Norway. When he calls Thule an island, is this because the world was not fully explored at the time.